Outlook Report: Mali

A key gold producer, Mali is at the centre of local conflicts and global rivalry.

Introduction

In the last year, Mali’s government has made some headlines worldwide for choosing Russia as a friend over the West. For years, however, a deeper and more substantial change is China’s displacement of France as the largest economic partner. This is key, as Paris still had an outsized influence in the region, through financial, diplomatic, and military means.

Mali is also paramount as a global leader in gold and cotton exports. However, it remains a very poor country, with a GDP per capita (PPP) of $2,447, while facing protracted armed conflicts and an array of political risks. Given the increased prominence of gold in global markets, the precious metal will be the core of the report, alongside an overview of the political and security situation. Climate risks will also play a critical risk, essentially as the country becomes increasingly arid, although they are not tackled in this report.

According to the IMF and the World Bank, Mali’s sovereign debt vulnerability is classed as “moderate risk of debt distress”. This is the most common category in the region. In March, the IMF highlighted that the fiscal deficit at 5% reflected an increase in spending for security, public wages and interest payments, which account for 80% of all expenditures. This is above the 3% deficit target of the West African Monetary Union, a condition set out by France. A key concern is that there is very little investment in infrastructure or public services.

Special note: In developing countries, it is especially difficult to obtain accurate data; analysts and investors must be fully aware of that. However, at Over the Hedge, we are best at putting together hard data and estimates to make the most reliable assessments. We always work with a combination of primary and secondary sources, taking into account the national government, local accounts, multilateral organisations, market actors, and others.

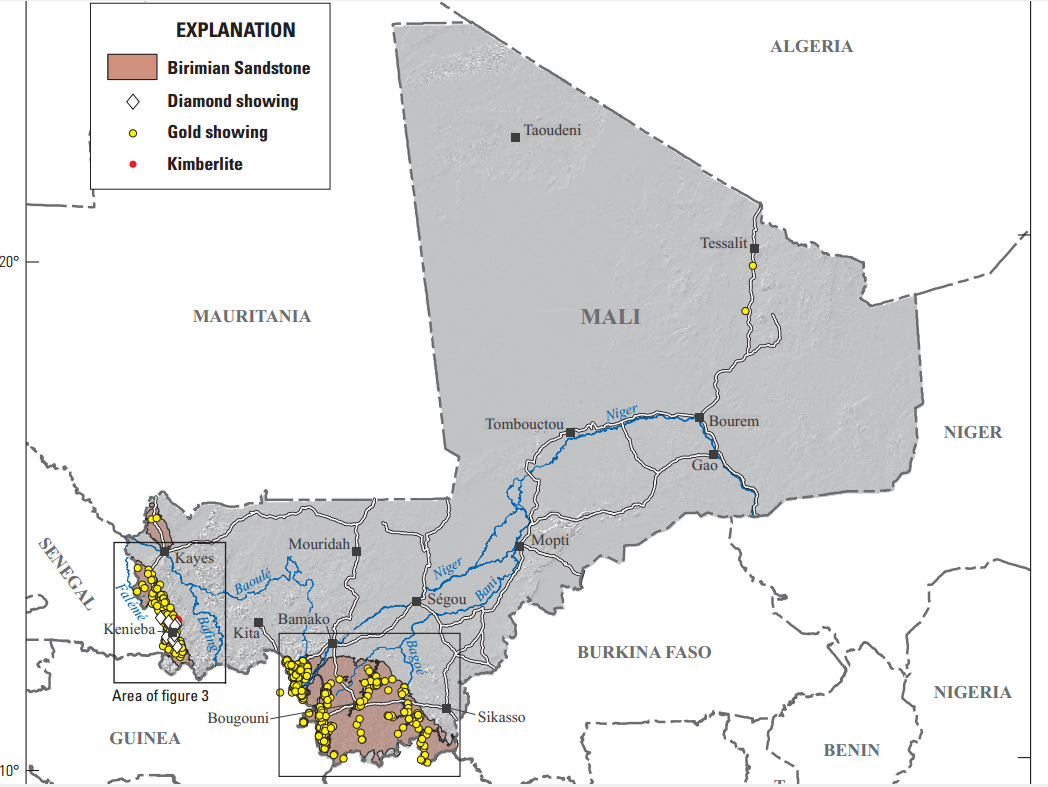

Gold industry

The key source of export revenues for Mali has been gold, the focus of this report. country is the third-largest producer of the precious metal, after Ghana and South Africa. It is estimated to have 800 tonnes of deposits, and in 2022 produced 65.2 tonnes. Production is dominated by corporations such as Canadians B2Gold (26%) and Barrick Gold (17%), and South African AngloGold Ashanti (2%). German Pearl Gold AG also holds a first participation Wassoul’Or, which is responsible for 9% of production. These operate in open pit large-scale industrial mines that produce the majority of the metal. There is also a significant artisanal mining sector, although it is hard to quantify and assess. State rents on resource extraction are much lower in Africa than in other developing regions. Nonetheless, in 2021 the Malian government raised $1.2bn in taxes from the mining sector – the country’s nominal GDP was $19.14bn in that same year.

While Western corporations still lead, the gold mining sector is drifting into the rivalling camp. The presence of the Wagner Group is not only related to security but also to mining activities, where it is also involved in other countries such as Sudan and the Central African Republic – although the full extent is difficult to assess.

In the last few decades, Dubai has become a central destination for Malian gold; the city has grown as a hub for sanctions evasion and illicit trade, as with the embargo on Russia. The Institute for Security Studies has pointed out sharp discrepancies in reporting between Mali and the UAE on their bilateral trade: “Although the UAE imported US$1.52 billion in gold from Mali in 2016, Bamako recorded only US$216 million in exports. Likewise, in 2014, Mali declared a gold production of 45.8 tonnes against the UAE’s import from Mali of 59.9 tonnes.” Mali and the UAE are also accused of rebranding gold from third countries, as could be the case with Venezuela and Libya. This January, representatives from Caracas and Bamako announced they intended to cooperate within the mining sector.

Agriculture

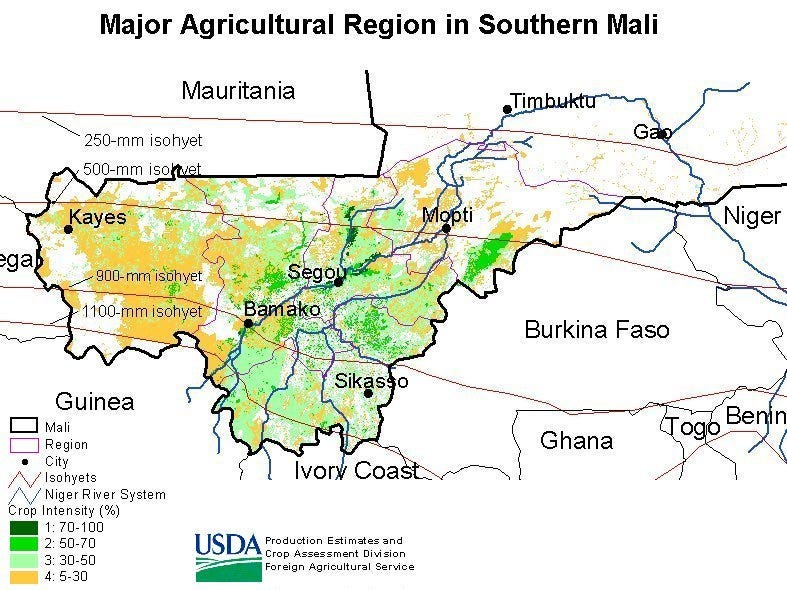

Mali is a largely agricultural society, employing between 70% and 80% of the population, and accounting for around 33% of GDP. The sector is difficult to quantify, especially regarding subsistence farmers. The country’s agriculture is also important beyond its borders, globally for its cash crops and regionally for its livestock.

In the world market, Mali has become a leading raw cotton exporter. If government announcements about the 2021-2022 harvest are accurate, it could have harvested 760,000 tonnes for the season. This makes the country the top producer in Africa and the 10th in the world. The president has pointed out that this achievement was possible with subsidies and the sharp rise in cotton prices in 2022. Since reaching a trough at the early point of the pandemic, the price of global cotton futures rose from $45 to $160 per pound by mid-2022, an all-decade high. Prices have since stabilised between $70 and $90, where they stood in 2018.

As explained below, Mali was sanctioned between January and July 2022. A key factor in the lifting of sanctions could have been the importance of Mali’s agricultural sector for the region. In the context of high food inflation, especially in African countries, there was extreme pressure to ease up. This happened just after Eid al-Adha, a Muslim festivity that traditionally involves the killing of a goat. At the time, pressure built up in surrounding countries over opening borders to let cattle exports out.

Sanctions and regional politics

Since 2019, Mali has experienced two military coups. The current government is currently led by Colonel Aissimi Goïta and other high-ranking officers – Goïta was vice-president under the previous coup government. Mali is part of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), which groups together former French colonies plus Guinea-Bissau. The community uses the West African CFA franc, which is pegged to the euro and follows a set of conditions from the French government. The region shares a central bank, the BCEAO, headquartered in Dakar, Senegal and a stocks and bonds exchange in Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

In January 2022, the ECOWAS community – which also includes countries like Nigeria and Ghana – sanctioned Mali, as Goïta’s government did not meet its conditions for a democratic transition. The move shut borders and cut off the country from financial markets and its central bank. This was an especially harsh blow for the landlocked country. Mali missed out on more than €330mn in bond payments. In July, after Goïta presented a new plan for future elections, sanctions were lifted. By August, the treasury was able to pay its arrears, in part by issuing new bonds worth €130mn.

Challenges: Security and conflict

Mali sits at the centre of tensions in the Sahel. Making a broad generalisation, there is a sharp divide between the North and the South of the country, which is present across the region. Particularly, there are tensions arising from conflicting livelihoods and cultures – between those who live in greener farmlands and pastoralists in more arid areas, between different peoples bundled together during colonisation, and so on. Disenfranchisement of communities has also played a role. In 2012, rebels in the northern region of Azawad revolted against the government in Bamako. Since, there has been fighting in the country. Insurgents have risen up as a “national liberation movement” or with religious branding. The latter factor has led to the framing of this war within the “War on Terror” – although it has no connection to attacks in Afghanistan or Europe. This narrative has nonetheless been used effectively to justify foreign intervention and aid packages from European countries and international organisations.

Since 2012, the Bamako government has been able to push rebels back thanks to extensive military aid and even foreign troops on the ground. France, alongside a multitude of friendly countries – such as Germany and Ivory Coast – made surges whenever insurgents gained too much ground. Currently, however, the situation could change drastically as France and its allies are withdrawing effective and peacekeeping personnel alike – though the latter not completely. Russian-led forces, including but not limited to the Wagner Group, could be more proactive than previous foreign powers. In another scenario, Moscow could be too bogged down in Ukraine to divert any significant resources to Mali.

A constitution is in the works

A new constitution is currently being finalised to be put to a popular vote. This initiative is led by the military government, although it seems to be well-received in much of the country. The structure set out for democratic functioning will be paramount. On this will depend whether sanctions are reimposed by the ECOWAS, or whether the government can once again receive aid from multilateral organisations.

The structure of the French-dominated monetary system is likely to change in the coming decade, although the initiative is currently coming from the government in Paris, which is seeing its economic influence wane in the region. France was historically the main trading partner not just for Mali, but for the region. In the last decade, however, China has taken that role. Beijing is yet to exert the same political influence as Paris nonetheless. Russian and Ukrainian exports are also significant, and neighbouring Senegal’s president has been an active voice in pushing for them to continue flowing into West Africa. Moscow is also penetrating into the region through diplomacy and offering security via the Wagner Group. The military governments of Mali and Burkina Faso have since called Russia an ally.