US Sanctions Driving Oil Supply Squeeze With OPEC+ Cuts

The Biden administration is worried that gasoline could rise to $5 a gallon.

On September 5th, the Brent crude price reached $90 a barrel, a price last seen in autumn 2022, with the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) benchmark close behind. The threshold was reached as Russia and Saudi Arabia reiterated their commitment to cut production and drive up prices.

The Biden administration is worried that energy costs could rise to bring gasoline at $5 a gallon, reigniting inflation and hurting its electoral prospects for 2024. Nevertheless, the White House could easily counter the pressure immediately by easing sanctions on Venezuela. Current measures have barred crude from the South American nation from the official market, and crippled production capacity.

On September 4th, Vitol CEO Russel Hardy said that he does not expect an increase in Venezuelan oil exports to shake up oil markets. Sceptics had argued that, beyond sanctions, Venezuelan management would be so inefficient that the country would take many years to reach the oil production benchmark of 1 million barrels per day (mbpd). Nonetheless, just by giving authorisation to ChevronCVX, Eni SpA, and Repsol SA to resume a limited scope of operations, production has risen to an average of 736,000 bpd in the first three quarters of this year, according to secondary sources cited by the OPEC. The averages in 2021 and 2022 were 553,000 and 675,000 respectively, according to the same sources. Official data from Caracas put the 2023 average at 808,000 bpd.

According to Francisco Monaldi, a Venezuelan economist based in Houston, “current capacity is probably 900,000 bpd, before any large-scale investment”. Monaldi is the director of the Latin American Energy Program at Rice University’s Baker Institute. There are only two rigs in operation, while in the decade before sanctions, the count hovered around 60. Monaldi also estimated that if sanctions are lifted, Venezuela could be producing 250,000 more in two years.

Monaldi contributed to the proposal of the Plataforma Unitaria, largest opposition alliance, where they planned to increase production by 2.1 mbpd in seven years. This would require lifting sanctions, an overhaul in regulatory framework to attract foreign investment “and not just changing the government but attaining political stability”. Monaldi also said that under Chavismo, Venezuela was producing well below its potential: “if we had sustained our share of the market from the 1990s, when we produced 3.3 mbpd -which we could have easily achieve- we would now be producing 5 mbpd.”

Jose Chalhoub, a political risk and oil consultant for Venergy, argues that in five years the Orinoco Belt region could produce 2 mbpd. This would likewise require lifting sanctions, extensive foreign investment, recovering abandoned wells and a complete reorganisation of the industry.

Saudi Arabia is attempting to tighten supply with a 1 mbpd cut, with the support of Russia which is reducing it by 300,000. Without accounting for differences in types of crude, lifting oil sanctions on Venezuela could be the single most effective way to offset the Riyadh-Moscow strategy. Reversing the “maximum pressure” strategy would unlock investment, allow the import of inputs, and put the South American country’s energy exports on the formal market. The White House, by executive order, is effectively enforcing the largest oil supply cut by targeting Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), the state-owned flagship fossil fuels enterprise.

How did sanctions affect Venezuela’s oil industry?

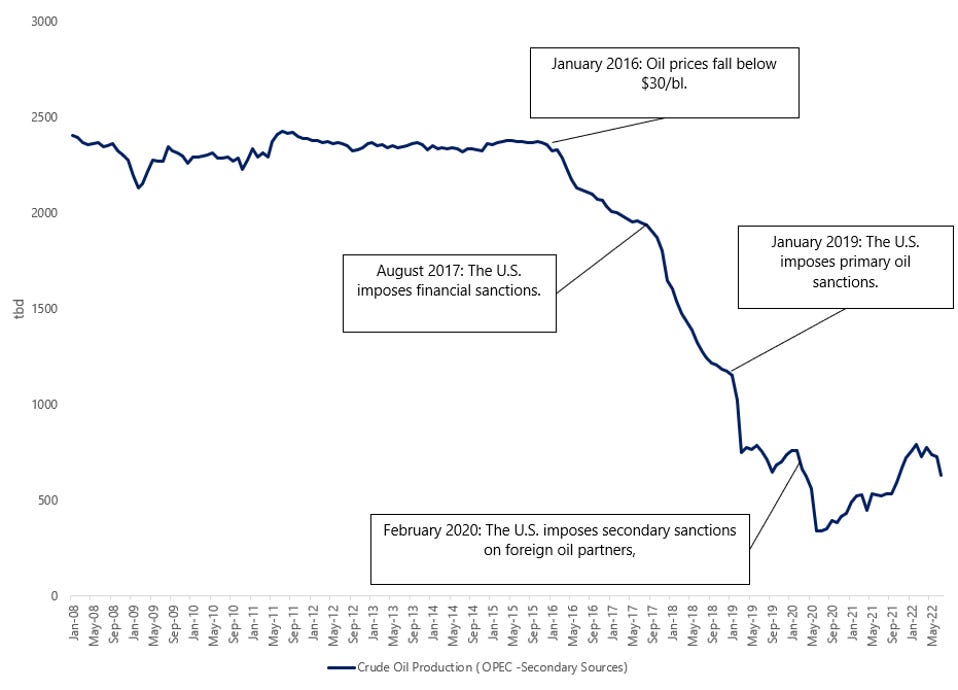

In 2017, US executive orders cut off both the Venezuelan state and PDVSA’s access to financial markets. From 2019, direct sanctions also blocked off PDVSA from selling to the US market, which was the largest single destination at the time, buying around 500,000 bpd. Rosneft as well as buyers from India, and Chinese state firms stepped in. However, in early 2020 the Trump administration also went after third parties, effectively pushing Venezuelan oil out of the official market. Crucially regarding oil, Washington DC seized CITGO Petroleum, PDVSA’s largest overseas asset, which owns refineries and gas stations in the US.

Francisco Rodriguez, a Venezuelan economist in Denver, is the author of several peer-reviewed publications and a forthcoming book dealing with the impact of sanctions on the Venezuelan economy. “Sanctions constituted a trade embargo on almost all Venezuelan exports” according to Rodriguez’s findings. “For the US it was clear that the Venezuelan economy was very vulnerable to restrictions on oil, given its high dependency on such exports”.

Rodriguez is the Rice Family Professor of Public and International Affairs at the University of Denver’s Joseph Korbel School. He also estimates that “sanctions explain 59% of the decline in oil production suffered after they were imposed on August of 2017.” While other causes such as mismanagement and falling oil prices from 2015 also damaged PDVSA’s capacity, sanctions take the lion’s share.

Experts consider that the main buyer is Chinese private firms, based on shipping data. Venezuelan oil needs to travel through a secretive and expensive process. Some techniques involve turning off radars at sea or transferring vessels in Malaysia. The opaque transactions with multiple intermediaries allowed for corruption to flourish; it is estimated around $3.6bn in unpaid invoices might never be recovered – although Reuter’s claim of $21bn is due to a misunderstanding of the original report.

Besides buyers, the Venezuelan energy sector is in desperate need for inputs, from machinery to diluents to experts. Under sanctions, they are increasingly hard to find; since the US Treasury Department can go after third parties, firms from across the world are either directly blocked from dealing with PDVSA or distance themselves due to overcompliance. European firms, such as Eni and Repsol, have needed authorisation from the US to first take oil shipments to pay off debt, and later to swap oil for fuel.

During 2022, as the Biden administration decided on giving a waiver to Chevron to resume operations, many analysts expected all Western energy firms to be included as well soon after. However, almost a year after it was granted, Chevron is in a privileged position while its competitors are still blocked. There seems to be no justification as to why the White House has made an exception for just one US corporation.

Foreign powers consider strategic investments

Experts are also considering possibilities created by foreign investment, especially if sanctions are partially or fully lifted. There are four key potential sources of capital and partnership for Venezuela’s energy industry: the US, Western Europe, China, and Iran.

Without Western involvement, Chinese investments could, albeit slowly, take their place. On September 5th, Vice President Delcy Rodríguez and Oil Minister Pedro Tellechea landed in Shanghai to discuss joint ventures. While sanctions and the economic crisis have also limited Chinese investment in the South American country, there are plans to up the ante. Minister Tellechea came to his post at the unveiling of the unpaid invoices scandal, and he is working with China National Petroleum Corporation to cut out middlemen and formalise trade.

Iranian help has also been essential for PDVSA; Tehran has learned to cope with sanctions for much longer. This year, Iran’s support has enabled refineries to resume operations, in a country where gasoline shortages have become periodic. Shipments from across the Strait of Hormuz have also sent condensate to dilute and upgrade the extra heavy crude found in the Orinoco Belt.

European firms are now looking for natural gas, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered a frantic search for alternative sources. In April Josep Borrell, the EU’s top diplomat, pointed out Venezuela’s natural gas potential, stating that it has “197 trillion cubic feet of proven reserves”, while it “burns 1.5 billion cubic feet of gas per day, equivalent to the consumption of medium-sized countries, which is catastrophic from both an economic and environmental point of view.” The proposed response is to turn the so far untapped natural gas sector into a productive industry. For the EU there are three key benefits: it would find an alternative source to Russia; the damaged Venezuelan economy would receive much needed revenues, and methane emissions would be reduced dramatically.

On September 5th, Reuters reported that Shell plc, Trinidad and Tobago’s National Gas Company (NGC) and PDVSA are close to reaching a deal on an offshore gas project. The $1bn investment had been stalled by the White House, which demanded there be no cash payments to Venezuela. Nonetheless, in January it was given the green light with a two-year authorisation. Shell and other UK-based multinationals could potentially face problems at home, however, as 10 Downing Street does not recognise Maduro’s administration as the legitimate government of the country.

Ultimately, most energy projects rely on the whims of US presidents, who can sign letters authorising or forbidding foreign firms from doing business in Venezuela. Even China and Iran are constrained, especially as global shipping is also targeted by the US Treasury, for example by removing vessels’ ability to access insurance. In light of tensions between China and the US, whoever sits in Caracas may have to pick sides, said Jose Chalhoub. If sanctions persist, the decision is already taken.